Python Function Parameters

Yeah, I know. You've been using python for more than a month. You know what a function is.

Seeing stuff like def log_message(message, level): doesn't scare you.

But what about def log_message(message, /, timestamp, *, level):?

Or how about def log_message(message, level, *args, **kwargs):?

Today, we're digging into function headers. We'll demystify what those asterisks and forward slashes do. Get ready to level up, Pikachu.

Level 1: Basics of Parameters

A function is like a loyal Pokémon: trained once, but ready to use again and again. You give it some input, and it makes a predictable move every time. Like this one:

def log_message(message, level):

ts_formatted = datetime.now().strftime("%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S")

print(f"[{ts_formatted}] [{level}] {message}")

Give a message and level, and a formatted log entry is printed:

>>> log_message("Hello World", "INFO")

[2025-06-25 16:30:24] [INFO] Hello World

The message and level are the function's parameters, or the "commands" the function expects to receive.

Quick side note: When we define a function, the inputs are called "parameters". But when we call the function, the values we actually give are "arguments".

The user must pass an argument for each parameter to call the function... except when there's already a default argument.

Level 2: Default Arguments

Parameters can have default values in the function header. Here's our modifed log_message, where level has a default argument of "INFO":

def log_message(message, level="INFO"):

# ^^^^^^ default argument

ts_formatted = datetime.now().strftime("%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S")

print(f"[{ts_formatted}] [{level}] {message}")

The user can give their own level, but if they don't, the default value is used. Now the function's easier to call; the user can enter just 1 of the 2 arguments:

>>> log_message("Hello World")

[2025-06-25 16:30:24] [INFO] Hello World

Before you start sprinkling your parameters with default arguments, be warned: Do NOT use a mutable object (like a list or dictionary) as a default argument. It's like leaving your Poké Ball open: something weird will crawl in there.

Default arguments are evaluated when the function is loaded, not when the function is called.

Let's look for errors in logged events. A reasonable attempt would loop through each log entry and store any errors in a warnings list. And someone (not you) would define an empty list ([]) as the default argument:

def process_events(events, warnings=[]): # DANGER HERE

for event in events:

if "error" in event:

warnings.append(error)

return warnings

It seems tame. But look what happens:

>>> # 1st batch

>>> events1 = ["ok", "error:missing_field"]

>>> process_events(events1) # expected: ['error:missing_field']

['error:missing_field']

>>>

>>> # 2nd batch

>>> events2 = ["error:bad_format"]

>>> process_events(events2) # expected: ['error:bad_format'] ... but we get

['error:missing_field', 'error:bad_format']

Hmm... How'd the 2nd call return errors found in the 1st batch? Both function calls share the same warnings list, which was not intended. That empty list was created when the function was defined, so every function call uses the exact same list object.

Here's a safer alternative that does what we want:

def process_events(events, warnings=None):

if warnings is None:

warnings = [] # this is defined for each function call (if needed)

for event in events:

if "error" in event:

warnings.append(event)

return warnings

Instead of an empty list, None is the default argument of warnings. If the user doesn't pass a warnings argument, the function defines warnings as an empty list at call time. This isolates the default empty list to a single function call (i.e. no shared state between calls).

Positional or Keyword Parameters

So far, our example parameters have received arguments by either position or keyword. The following function calls are all valid:

def log_message(message, level):

ts_formatted = datetime.now().strftime("%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S")

print(f"[{ts_formatted}] [{level}] {message}")

log_message("Hello World", "INFO") # positional arguments - just type input value, not parameter name

log_message(message="Hello World", level="INFO") # keyword arguments - type "name=value"

log_message(level="INFO", message="Hello World") # keyword arguments (but different order)

log_message("Hello World", level="INFO") # mixture of positional and keyword arguments

When using positional arguments, order matters. The argument order in a function call must match parameter order in the function header.

However, when using keyword arguments, the order does not matter. Python will pass the argument to the correct parameter. The only restriction is that keyword arguments must appear after positional arguments.

But sometimes, you want more restrictions on how your function is used.

Level 10: Positional-ONLY and Keyword-ONLY Parameters

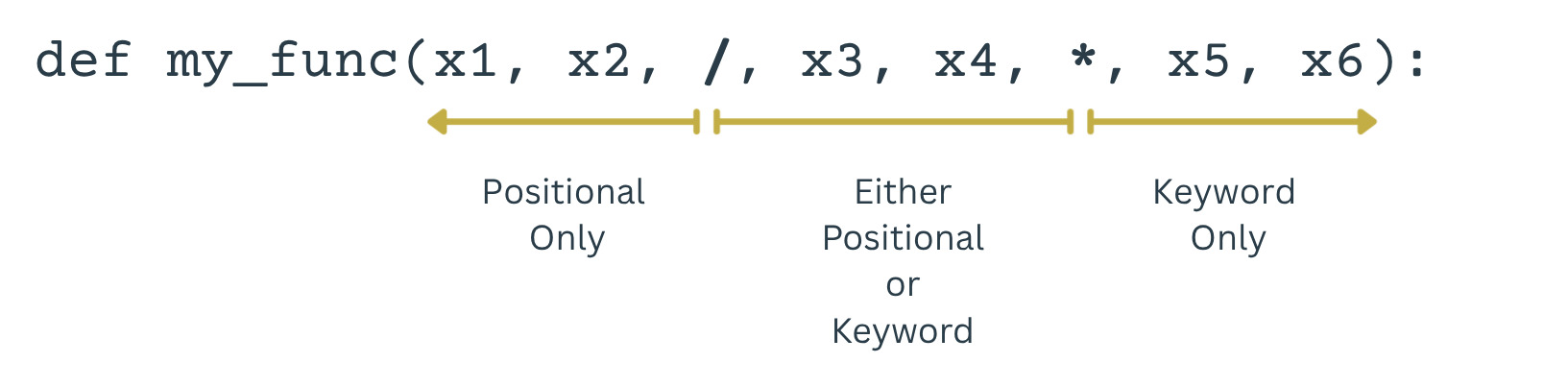

Let's talk about that / and * in the function header. These markers force a parameter to be positional-only or keyword-only.

The markers break the function header into three "regions" of parameters:

A parameter before the / marker must receive an argument by position, not by keyword. Why would that be useful, you ask?

Well, maybe the order of arguments is meaningful. Consider the function make_point(x, y) which creates a point in the Cartesian coordinate system. (Did you feel that high school algebra nostalgia?) We know "x" appears before "y" on paper, so it's silly to let the user change the order with something like point(y=-4, x=5). To force consistent argument ordering, we use the / marker:

def make_point(x, y, /):

print(f"Point ({x}, {y}) created")

Now, if our user tries to switch the order using keyword arguments, they'll get an error:

>>> make_point(y=-4, x=5)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<input>", line 1, in <module>

make_point(y=-4, x=5)

~~~~~~~~~~^^^^^^^^^^^

TypeError: make_point() got some positional-only arguments passed as keyword arguments: 'x, y'

The function will only accept positional arguments, like make_point(5, -4). This is more of a stylistic choice when designing your function. You force users to pass arguments in a way that avoids confusion: the 1st argument is always "x"; the 2nd argument is always "y". As a bonus, you can change the parameter names without breaking any user code.

Next, parameters after the * marker must receive arguments by keyword, not by position. This makes function calls more readable, especially when the function has many parameters. Check out this email-sender function:

def send_email(to, subject, cc, bcc, reply_to):

...

Imagine how a user may call it:

>>> send_email('hermione@hogwarts.edu', 'I love you', 'harry@hogwarts.edu', 'molly@alumni.hogwarts.edu', 'ron@hogwarts.edu')

Uh... who's CC'd on this email and who's BCC'd? It's hard to tell what each argument means. Instead, you can require keyword arguments with the * marker.

def send_email(to, subject, *, cc, bcc, reply_to):

... # ^^ ^^^ ^^^^^^^^ These guys must have keyword arguments now

Now, if our function is called without keyword arguments, an error is raised:

>>> send_email('hermione@hogwarts.edu', 'I love you', 'harry@hogwarts.edu', 'molly@alumni.hogwarts.edu', 'ron@hogwarts.edu')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<input>", line 1, in <module>

send_email('hermione@hogwarts.edu', 'I love you', 'harry@hogwarts.edu', 'molly@alumni.hogwarts.edu', 'ron@hogwarts.edu')

~~~~~~~~~~^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

TypeError: send_email() takes 2 positional arguments but 5 were given

But this call will pass:

>>> send_email('hermione@hogwarts.edu', 'I love you',

... cc='harry@hogwarts.edu',

... bcc='molly@alumni.hogwarts.edu',

... reply_to='ron@hogwarts.edu')

This version clearly shows what the last few arguments map to.

Keyword-only parameters also allow future changes with minimal risk of argument-ordering bugs. Maybe one day, the function will have a keyword-only "encrypt" parameter. Your can safely rearrange the order of keyword-only parameters without breaking existing code:

def send_email(to, subject, *, encrypt, cc, bcc, reply_to):

# ^ "encrypt" can safely squeeze in before "cc"

# since these parameters are keyword-only

...

When picking a parameter type, remember the following:

- Use position-only parameters when the order of arguments is important or the parameter names may change in the future.

- Use keyword-only parameters to improve readability when the function is used and to add new parameters without breaking code.

- Use positional-or-keyword parameters when it doesn't make a difference.

Level 25: Variable Parameters

Sometimes, you just don't know. You don't know how many arguments a function will receive in the wild. Luckily, you can use the *args parameter to group extra positional arguments into a tuple:

>>> def func(x, y, *args):

... print(f"{x=}, {y=}, {args=}")

...

>>> func(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

x=1, y=2, args=(3, 4, 5)

Notice our function has positional parameters x and y. But when we called the function, we passed 5 arguments. Python took the first two positional arguments and gave them to x and y; the rest of the positional arguments were shoved into a tuple called args.

Likewise, sometimes your function will receive a variable number of keyword arguments. Use the **kwargs parameter to gather extra keyword arguments into a dictionary:

>>> def func(x, y, **kwargs):

... print(f"{x=}, {y=}, {kwargs=}")

...

>>> func(1, 2, a=3, b=4, c=5)

x=1, y=2, kwargs={'a': 3, 'b': 4, 'c': 5}

This time, we're passing some keyword arguments not defined in the function header. Python will capture these undeclared keyword arguments and store them in a dictionary called kwargs.

Note: The parameter names "args" and "kwargs" are not required. You can use any variable name, like *stuff and **more_stuff, but "args" and "kwargs" are the community accepted standard. It's the unpacking operator (* and **) before the parameter name that performs the magic.

Here's a more practical example of how variable arguments can enhance our log_message function. *messages and **metadata join the team:

def log_message(*messages, level="INFO", **metadata):

ts_formatted = datetime.now().strftime("%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S")

meta_str = " ".join(f"{k}={v}" for k, v in metadata.items())

for message in messages:

print(f"[{ts_formatted}] [{level}] {message} {meta_str}")

Now we send multiple events to log_message. Any extra info is passed as keyword arguments and stored in metadata to enhance the message:

>>> log_message(

... "Disk usage at 85%",

... "Auto-scaling triggered",

... level="WARNING",

... instance="vm-123",

... region="us-east-1",

... )

[2025-06-30 15:52:01] [WARNING] Disk usage at 85% instance=vm-123 region=us-east-1

[2025-06-30 15:52:01] [WARNING] Auto-scaling triggered instance=vm-123 region=us-east-1

Whew! You made it! Here's your treat: A cheatsheet of the parameter types.

| Parameter Type | Example Definition | Must Be Called As |

|---|---|---|

| Positional-only | def f(x, /) |

f(1) |

| Positional-or-keyword | def f(x) or def f(x=1) |

f(1) or f(x=1) |

| Keyword-only | def f(*, x) |

f(x=1) |

| Variable Positional | def f(*args) |

f(1, 2, 3) |

| Variable Keyword | def f(**kwargs) |

f(x=1, y=2) |

Just like choosing your starter Pokémon, how you define your parameters sets the tone for the whole adventure. Letting your parameters be positional-or-keyword is usually fine. However, enhancing functions with other parameter types can make larger modules more prepared for what life (i.e. users) may throw at it.

What other ways do you use function parameters? Give me a shout if you want to take your functions to the next level.