Python Slicing

All sequences can be sliced.

Boy, that was a boring sentence. What are we talking about?

- A sequence can be a string, list, tuple, or set in Python. It's any ordered collection of objects.

- A "slice" of a sequence is part of that sequence.

Many use this Python feature, but few understand slicing beyond the basics. Today we'll refresh our knowledge of slicing and see some advanced uses.

Let's start with an example. Here's my grocery list:

>>> grocery_list = ['eggs', 'milk', 'goldfish', 'apples', 'ramen noodles']

I know... I eat like a king.

Basics

Take off your floaties. I'm throwing you into the deep end of the pool. Figure out how slicing works:

>>> grocery_list[0] # first item

'eggs'

>>> grocery_list[2:4] # 2nd and 3rd items

['goldfish', 'apples']

>>> grocery_list[:2] # first 2 items

['eggs', 'milk']

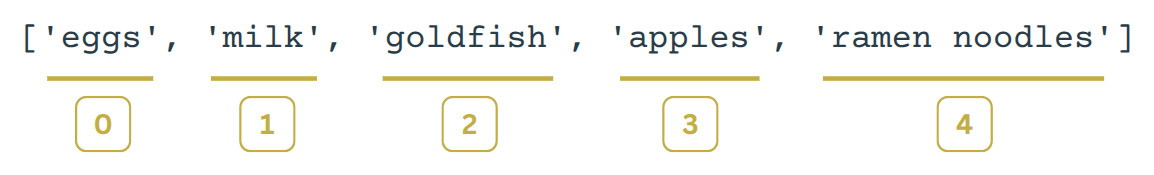

You may guess that the [] after the variable is used to get some part of the list. What you put into this indexing operator ([]) determines what you get back out. Each item in a sequence has an index, or a special number that identifies its position. The first item has an index of 0, the second item has an index 1, and so on:

Passing a single number into the indexing operator ([]) gives you the item in that position. Including two numbers with a colon between them gives you all items in that index range, excluding the last item.

If you use a colon and omit a number, Python will extend the range to the beginning or end.

- For example,

grocery_list[:2]gives items from the beginning to index 2. grocery_list[1:]gives items from position 1 to the end of the list.- Unsurprisingly,

grocery_list[:]returns all items.

But wait, there's more! You can skip over items by passing a "step" value after another colon. Get back into the deep end:

>>> grocery_list = ['eggs', 'milk', 'goldfish', 'apples', 'ramen noodles']

>>> grocery_list[0:4:2] # every other item between 0th and 3rd item

['eggs', 'goldfish']

>>> grocery_list[1::3] # every 3rd item beginning with 1st item

['milk', 'ramen noodles']

The complete form of an index operator is [start:stop:step]. Use different combinations of these 3 numbers to frolic through your sequence however you wish.

Negative Slicing

Let's say you want something from the end of the list. But you don't know how long the list is or the index values for the last few items.

You know the drill; jump back in:

>>> grocery_list[-1] # last item

'ramen noodles'

>>> grocery_list[-3:] # last 3 items

['goldfish', 'apples', 'ramen noodles']

>>> grocery_list[::-1] # entire list in reverse

['ramen noodles', 'apples', 'goldfish', 'milk', 'eggs']

Negative indices identify items from the right, not the left. Similarly, a negative step value reads the sequence backwards.

Here's the more complete view of the two index frameworks. Either can be used the extract part of a sequence:

Behind the Scenes

Two things happen when you use the [] operator on a Python sequence:

- Python generates a

sliceobject. - That

sliceobject is sent to the sequence's__getitem__method. It's up to the logic of__getitem__to do something with thesliceobject.

Most people ignore this... or don't care. But you're not like most people. You're a hacker who uses slice objects to make life easier.

While slice objects are used implicitly via the [] operator, they can be used explicitly in your code. Let's check out two examples.

Ex 1: Data Engineering Application

If you're blessed, you receive data in neat formats with no issues. If not, you're a data engineer who ingests text files like this:

1001 Nimbus 2000 $500.00 1

1002 Cauldron $20.50 17

1003 Chocolate Frogs $3.75 127

I don't know why, but someone thought sending orders with fixed column lengths was a good idea. We have to deal with it.

The file could be processed by breaking each line into columns. The start and end position of each column could be passed to the indexing operator:

orders = """\

1001 Nimbus 2000 $500.00 1

1002 Cauldron $20.50 17

1003 Chocolate Frogs $3.75 127"""

# process each line

for item in orders.split("\n"):

print(

item[:10].strip(),

item[10:35].strip(),

float(item[35:43].strip().replace("$", "")),

item[43:].strip(),

)

Look at all those indices you have to keep track of (10, 35, 43, ...). Now imagine having hundreds of columns with unhelpful numbers to identify them.

Here's a better world, one that uses slice objects:

# define column boundaries as slice objects

ORDER_ID = slice(None, 10)

DESCRIPTION = slice(10, 35)

UNIT_PRICE = slice(35, 43)

QUANTITY = slice(43, None)

# process each line

for item in orders.split("\n"):

print(

item[ORDER_ID].strip(),

item[DESCRIPTION].strip(),

float(item[UNIT_PRICE].strip().replace("$", "")),

item[QUANTITY].strip(),

)

The slices are defined once with helpful variable names at the beginning. These slice objects have "start" and "end" positions to mark the boundaries of each column. Then the variables are used to process the file. This makes debugging large files easier and improves readability. After all, item[UNIT_PRICE] makes more sense than item[35:43].

Ex 2: Slicing Your Own Class

Let's write a class to track spells we've learned. We'll use slice objects to look up spells by their first letter.

The class below features a method get_spell_by_first_letter which does the obvious; it returns a list of spells that begin with any letters it receives. The real magic is in the __getitem__ method.

import string

class SpellBook:

def __init__(self):

self.spells = []

def add_spell(self, incantation):

self.spells.append(incantation)

def get_spell_by_first_letter(self, letters):

search_results = []

for spell in self.spells:

if any(spell.startswith(letter) for letter in letters):

search_results.append(spell)

return sorted(search_results)

def __getitem__(self, search_key):

if isinstance(search_key, str):

return self.get_spell_by_first_letter(search_key)

if isinstance(search_key, slice):

start, stop, step = search_key.start, search_key.stop, search_key.step

index_start = string.ascii_uppercase.index(start)

index_stop = string.ascii_uppercase.index(stop) + 1

range_of_letters = string.ascii_uppercase[index_start:index_stop:step]

return self.get_spell_by_first_letter(range_of_letters)

# create spell book and add spells

spell_book = SpellBook()

spell_book.add_spell("Flipendo")

spell_book.add_spell("Riddikulus")

spell_book.add_spell("Bombarda")

spell_book.add_spell("Expelliarmus")

spell_book.add_spell("Petrificus Totalus")

spell_book.add_spell("Locomotor Mortis")

spell_book.add_spell("Wingardium Leviosa")

Here, we've instantiated our spell_book and stored our favorite spells.

When the index operator on spell_book receives a letter (e.g. spell_book["B"]), the spells beginning with that letter are returned.

But when the index operator gets something in a slice format (e.g. spell_book["A":"L"]), Python converts that into a slice object (slice("A", "L", None)) and passes it to __getitem__. The logic within __getitem__ identifies the range of letters between the start and stop letter; then get_spell_by_first_letter is called. The returned value is a list of spells beginning with the letters in that range.

>>> spell_book["B"] # get spells beginning with "B"

['Bombarda']

>>> spell_book["A":"L"] # get spells beginning with letters between "A" and "L"

['Bombarda', 'Expelliarmus', 'Flipendo', 'Locomotor Mortis']

The core magic of this __getitem__ is converting two letters it receives into a range of letters. This is done by catching the slice object and bending its contents to fit our needs.

Perhaps you've written custom classes of your own. Including a well-defined __getitem__ method can make your class instances slicable and improve user experience.

Python's a great language because it's easy to get started with. In your early lessons, you likely built sequences and sliced them with the [] operator. Unfortunately, you probably moved on to other topics without seeing more advanced slicing scenarios. It's good to revisit the basics and dig deeper.

Go forth and use your new slicing magic. If you want a coach while you swim in the deep end, you know where to find me.